![]()

Ganbat Damba[1], Mina Sumaadii[2]

Academy of Political Education

1. Introduction

The 1992 Constitution is considered the “blueprint of Mongolia democracy” (Sanders 1992). This Constitution has served Mongolia’s democracy well, as to date, eight electoral cycles have been held regularly, yielding uncertain outcomes and fostering multiparty competition for the people’s votes. In the Varieties of Democracy Project’s liberal democracy index, Mongolia started with a score of 0.41 in 1991 and, with slight fluctuations, ended with a score of 0.49 in 2021 (V-Dem Project 2022). At its height, it reached 0.61 in 1999. This reflects that Mongolia’s road to democratic development was not smooth and had its ups and downs. Nonetheless, these scores consistently place Mongolia in the “electoral democracy” category. While this is an accomplishment in comparison to other post-communist states in the region, it is still a democracy which has institutional challenges and much room for improvement.

Based on this, this report examines the internal structure of Mongolian democracy from the point of institutional checks and balances that exist under the constitutional setting. Therefore, we present a concept of horizontal accountability, which is part of a series of constraints on government use of political power. In the Mongolian media and political discussions, horizontal accountability is not a commonly used term. As one of the cornerstones of good governance, it measures the extent to which the government is accountable to other branches (Lührmann et al 2017). This is a particularly important issue for Mongolian governance to address, given the scope of reforms that shifted the domestic power balances among the government branches in recent years. Moreover, due to the low level of trust in public institutions and a lack of belief in the impartiality of politicians (Sant Maral Foundation 2023), the public is increasingly turning to protests as a preferred measure to hold the government accountable. Overall, this suggests that citizens no longer have the patience to rely on institutional checks and balances to represent or defend public interests; instead, they are increasingly inclined to take matters into their own hands.

As a result, addressing the related governance issues is becoming an increasingly important task for the quality and durability of Mongolian democracy.

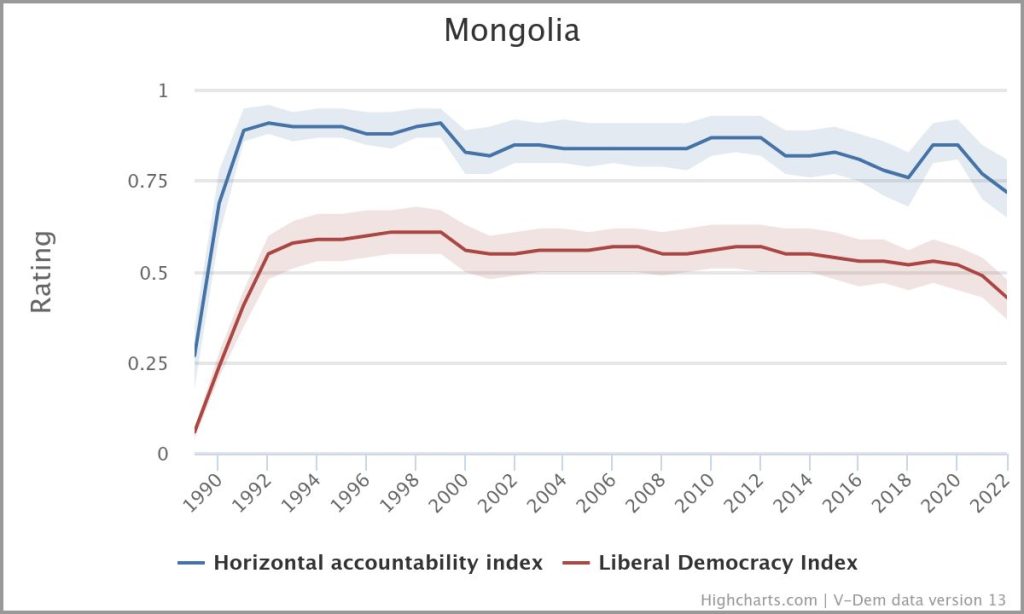

The V-Dem Project traces that the horizontal accountability index (scaled low to high (0-1)) in Mongolia had a score of 0.9 in 1991 and throughout the remainder of the 1990s (V-Dem Project 2022). Yet, it decreased following each constitutional amendment in 1999/2000 and 2019. Eventually, after fluctuations, it ended with a score of 0.78 in 2021 (V-Dem Project 2022). While in the broader historical context, the scores in the last three decades are at their highest level since Mongolia transitioned to democracy, the gradual decrease in the horizontal accountability index follows the general trend of declining government accountability.

Figure 1. Horizontal accountability and Liberal Democracy Indices in Mongolia

Source: V-Dem Project

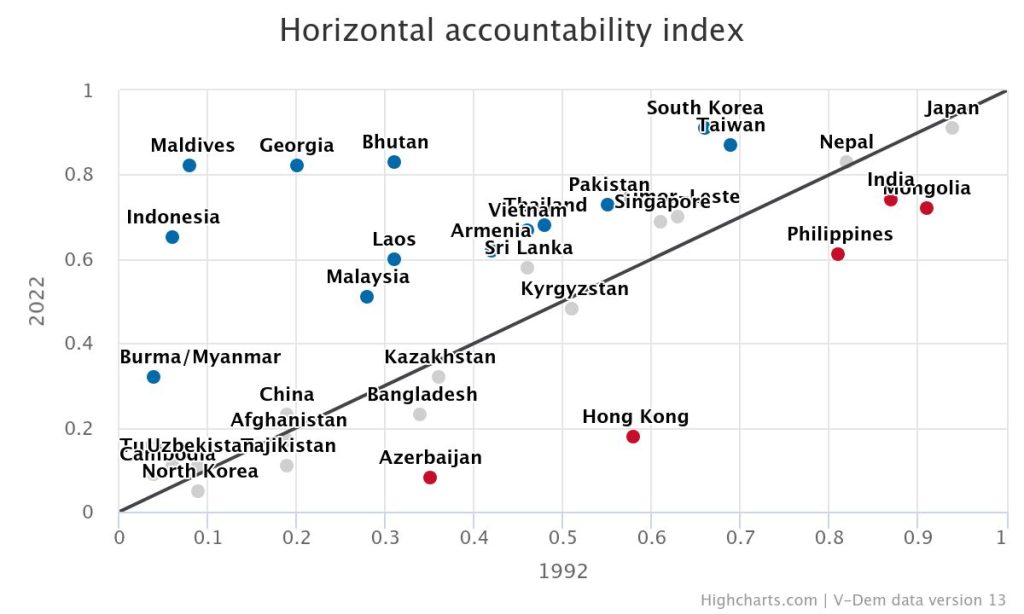

Regionally, Mongolian performance in horizontal accountability can be considered to be relatively high. While it is not at the level of advanced democracies, it performs better than countries within a similar income group. Based on the regional comparison of horizontal accountability, it can be seen that since the introduction of the 1992 Constitution, Mongolia’s position and decline are the most similar to India and the Philippines. Among these cases, the most important factor linked to the decline in horizontal accountability is the continuous weakening of judicial independence (See Reports on India and the Philippines). Similarly, Mongolia’s judicial branch struggles to maintain its independence following a series of constitutional and legal reforms. Moreover, in the existing political environment, oversight agencies have limited capacity and are not free from political interference. As a result, the constraints on the legislature and executive officials are weak.

Figure 2. Regional Comparison of Horizontal Accountability Index

Source: V-Dem Project

In cross-country research, Sato et al. (2022) found that in the process of autocratization, institutional decay starts with horizontal accountability, followed by declines in diagonal accountability, and ultimately vertical accountability. According to recent developments, some early signs of democratic erosion can already be found in Mongolia. As the balance of power between different branches becomes uneven, we will address some of the issues of concern, potentially pointing out some general prescriptions that can counter the process. Further investigation can also offer an institutional explanation of Mongolia’s good democratic performance and ineffective governance.

The main conclusion of the current cross-country research is that if a country has better horizontal accountability, then the quality of its democracy can be improved. At the same time, if there is erosion of horizontal accountability, the quality of democracy will deteriorate. Based on longitudinal observations by the V-Dem project, we can see that the decline in horizontal accountability is correlated with the decline in the quality of Mongolian liberal democracy.

Consequently, to uncover the factors contributing to this trend, the study is organized as follows. We begin with an assessment of Mongolia’s de jure and de facto horizontal accountability from a comparative perspective. It is followed by the introduction of a constitutional checks and balances system in Mongolia. Next, we describe the existing hierarchy of power among the government branches, followed by the description of recent constitutional amendments and their outcomes on political power distribution. Then, we address the legal procedures available to counterbalance the misconduct found in each government branch. After that, we assess the judicial branch’s independence in more detail. Finally, we examine oversight agencies and their capabilities and conclude the study.

2. Mongolia in the Comparative Context

This study aims to assess the factors related to the recent trends in democratic decline in Mongolia. As evidenced by the data, most changes were gradual and would require an investigation that starts by the introduction of the 1992 Constitution that institutionalized democracy. In addition, there are formal and informal factors that are involved in the process. Thus, analytically, it is useful to separate de jure and de facto horizontal accountability.

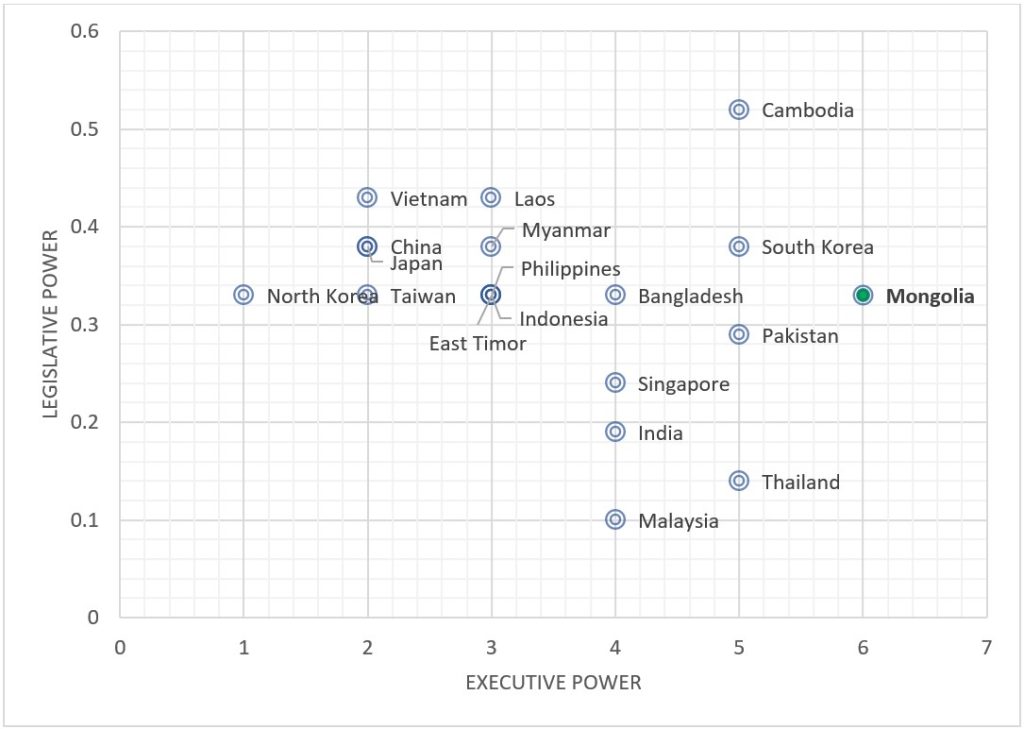

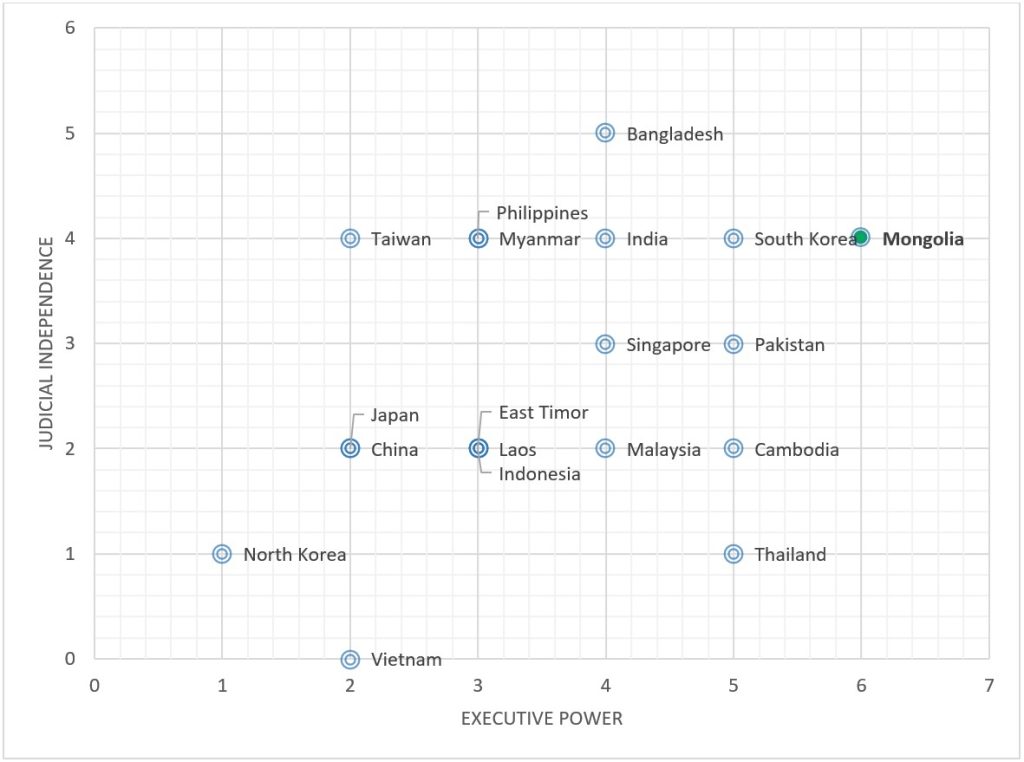

De jure horizontal accountability describes how much power does the Constitution assign to the executive, legislative and judicial branches. It is going to be based on the Comparative Constitutions Project’s executive power indicator, legislative power indicator, and judicial independence indicator (Elkins et al 2022). The indicators based on the 1992 constitution show that the executive power was considerable, scoring 6 on a scale ranging from 0 to 7. The legislative power index was 0.33 on the range of 0 to 1, which indicates less legislative power. Figure 3 shows that regionally, Mongolian executive power is quite considerable, while the legislative power is at an average. It can be seen that the executive power is measured to be more extensive than in Cambodia, South Korea, Pakistan, and Thailand. Moreover, Figure 4 shows that Mongolia scores 4 for judicial independence in the range from 0 to 6, which can be considered average within the region.

Figure 3. Executive Power vs. Legislative Power

Source: Data from the Comparative Constitutions Project

Initially, the Mongolian Constitution introduced a balance between the executive and legislative branches. Thus, prior to amendments, Mongolian legislative and executive powers were relatively balanced. In contrast, the judicial branch’s powers were set to be weaker from the beginning. Further constitutional amendments mainly upset the balance between the executive and legislative powers, leading to the current setting where the legislative branch is dominant, and the other two branches are weak.

Figure 4. Executive Power vs. Judicial Independence

Source: Data from the Comparative Constitutions Project

Given this, it is important to mention that the executive branch in Mongolia is complicated, and in the future analyses, it would be necessary to distinguish the situation before and after the 2019 constitutional amendments. Prior to the amendments, there was an ambiguity about who was the head of the executive branch, as there was a considerable overlap between the president and the prime minister. Specifically, the Constitution explicitly states that the cabinet, led by the prime minister, is “the highest executive organ of the State” (Article 38.1). Yet the president’s role in appointments and legislative initiative implies executive power (Article 33.1). Notably, the 2019 amendment ended this ambiguity by expanding the prime minister’s powers to fully form the cabinet, clarifying that the prime minister is henceforth the head of the executive branch. Future indices may need to reflect this change.

Nonetheless, as we focus on the general situation and consider the president as the head of the executive, it should be noted that the powers given to the president as the national executive are significantly constrained. For that, we are going to break down the executive index in more depth. The index is additive and is composed of seven aspects that measure presence or absence of certain presidential powers. The first aspect measures the power to initiate legislation and is present (Article 26.1). The second involves the power to issue decrees and is also present. Even if the president has the power to issue decrees, the Constitution specifies that a co-signature of the prime minister is necessary for it to be effective (Article 33.1.3). Despite this, in the Mongolian Constitution, both powers are considerably constrained by the president’s lack of budgetary powers. Thus, regardless of the aspirations, it is improbable that any of the presidents’ initiatives will be realized unless they receive legislative support.

The third measurement includes the power to initiate amendments, and it is also constrained, as the president can only initiate constitutional amendments together with “the competent organs or officials with the right to legislative initiative”, or more specifically, “The President, Members of the State Great Hural (Parliament), and the Government (Cabinet)” (Articles 68.1 and 26.1). The fourth measurement covering the power to declare states of emergency is present; however, it is also constrained by the legislature’s decision to endorse or invalidate it (Article 33.1.12). The fifth measurement on veto power is present in Mongolia, but it is limited by the parliament’s ability to override it by two-thirds of its members (Article 31.1.1). The sixth power to challenge the constitutionality of legislation is absent, as this power is reserved to the Constitutional Court (Tsets). The seventh includes the power to dissolve the legislature. This power is also limited as Article 22.2 specifies that the president can only do so in concurrence with the speaker.

Following from this, there are multiple conditions in the Constitution that introduce controls over the presidential power. Particularly, six of the index’s seven powers are present, but all of them are constrained either directly by the legislative branch or indirectly through budgeting. As a result, the veto is the most significant power of the presidency due to the president’s ability to use it repeatedly and bring public attention. Therefore, we suggest that there are limitations in the index’s ability to capture the nuances of the executive power and, as a result, the president’s role in the checks-and-balances can be overestimated. Based on the current indices from the Comparative Constitutions Project, it may seem that the Mongolian executive branch is dominant and is an outlier in the region. Especially, as it shows that the Mongolian president is even more powerful than in South Korea, which has a presidential system. However, considering all the constraints included in the Mongolian Constitution and recent amendments, the reality is quite different. Thus, the indices would have to be updated to reflect the new setting.

In the end, the 2019 constitutional amendments have significantly changed the equilibrium established by the 1992 constitution. As a result of the continuous shift of power toward the legislative branch following the 1999/2000 and 2019 amendments, the legislative branch became the most dominant. As a result, the relationship between the three branches became unbalanced with the power predominantly concentrated in the legislature. This imbalance has been further exacerbated by the significant weakening of executive power through the new limits imposed on the presidency.

Specifically, the executive powers of the president have been considerably reduced by an introduction of a single term, higher age, and a reduced role in the judicial appointments. In particular, these changes have decreased the incentives for an active role in inter-branch power relations. In the past, the prospects of re-election made presidents more likely to pursue their own agenda, but since 2019, the shift to a one-term (6 years) presidency has diminished initiatives for political activism. As for the judicial branch, despite the constitutional declaration of its independence, its original design that made higher-level judges and prosecutors political appointees introduced a loophole. Considering a more comprehensive overview of powers, the 1992 constitutional design balanced the executive and legislative powers while leaving the judicial power with an in-built weakness of these political appointments. After the recent amendments though, the balance tilted the following way:

To summarize, in terms of de jure horizontal accountability, the 2019 constitutional design in Mongolia lacks balance. While the original 1992 constitution established a good structure for avoiding the concentration of power in one particular branch, the subsequent amendments in 1999/2000 and 2019 changed this balance. After the amendments, the legislative power is dominant, and due to the existing imbalances, it cannot be adequately checked by the executive and judicial branches. Adding to the issue is that major oversight agencies are not free from political interference. This could also explain the decreasing levels of horizontal accountability and the corresponding decreases in the levels of liberal democracy (Figure 1). Altogether, this leads to the conclusion that de facto horizontal accountability is even lower than de jure accountability. The following sections will focus more on domestic-level power arrangements to further elaborate the case.

3. Checks and Balances

The 1992 Constitution introduced a semi-presidential form of government. This power arrangement resulted in constant power struggles between the president’s office, the prime minister and his cabinet, and the parliament. This constitutional arrangement is credited with setting the Mongolian democracy on a long-term structural advantage among democratizing post-communist states overall (Fish 1998). On the positive side, during Mongolia’s transition to democracy, no branch could monopolize power, which became a positive institutional arrangement preventing it from drifting to authoritarianism seen in the former Soviet Union states in Asia (Fish 2001). However, on the negative side, this arrangement can lead to power disputes and political deadlocks during cohabitation (the president and the majority parliamentary party from opposing parties) and divided governments.

Historically, the most prominent example occurred when disputes between different government branches paralyzed the parliamentary term from 1996 to 2000, contributing to debates about the political stability or functionality of the democratic system. However, changing this system was never a popular idea based on opinion polls, as most of the population supported democracy as a form of governance (Sant Maral Foundation 2023). Therefore, the introduction of the first constitutional amendments partially addressed constitutional conflicts. Such political deadlocks during cohabitation and later coalition governments align with the general research on semi-presidential systems.

In the first place, the 1992 Constitution’s institutional equilibrium introduced an overlap between the president’s office, the prime minister, and the parliament. The design was based on the principles of checks and balances among different branches of government that relied on coordination. In practice, the Constitution relied on ‘consensus’ among the executive and legislative branches; an aspiration too difficult to achieve during periods of divided governments and cohabitation in a new democracy. This consensus or concurrence (depending on the translation) between the president and parliament was explicitly required in many articles in the 1992 Constitution, but later most of them were reversed by amendments in 1999/2000 and 2019. Moreover, the absence or underdevelopment of institutions to ensure the continuity of policies exacerbated the debates about stability and functionality.

Eventually, two major constitutional amendments were introduced to remedy some of these institutional conflicts. As a solution, they shifted the balance of power from the president to the parliament. While the decision is based on an argument that such shifts reduce the possibility of strongman politics associated with an all-powerful president, due to one-party dominance, it still led to a power concentration with an all-powerful parliament and prime minister. As a result, the previous balance of power between different branches of government became uneven, and the institutional equilibrium that has served Mongolian democracy well since 1992 has changed. It is still early to assess whether this is a positive or negative development, as further constitutional amendments and reform are being discussed. Yet, some recent developments such as the constitutional amendment in August 2022, Cyber Security Laws, and Human Rights Laws are causing concerns, with the abrupt introduction of legislation without public discussion or minimal oversight.

In the constitutional design, the separation of power in the legislative and judicial branches is clear. According to Article 20, the unicameral parliament, the State Great Khural, holds the legislative power. Article 47.1 states that courts and the Supreme Court exercise judicial power. However, the executive branch was always more ambivalent due to an overlap between the president and the prime minister. Article 38.1 of the Constitution explicitly states that the cabinet, led by the prime minister, is “the highest executive organ of the State.” Yet, the president’s role in appointments and legislative initiatives given by Article 33.1 implies executive power.

4. Hierarchy of Power

Despite legal ambivalence on the exact political hierarchy and significant constitutional limitations, the presidency is considered the top of the political establishment. This is because the presidency symbolizes the apex of political power in Mongolia, backed by a direct national vote and the popular legitimacy it confers, thereby rendering other state positions as somewhat subordinate. It is disputable whether the second highest position is the prime minister or the chairman (speaker) of parliament. Constitutionally, the prime minister is a much more powerful position than the presidency and is more visible to the public. Following the constitutional amendments in 2019, it became clear that the prime minister is the head of the executive and holds most of its powers. For example, in cases where there is no consensus on the structure and composition of the cabinet with the president, the prime minister can form his own cabinet by only presenting it to the parliament and president (2019 amended version Article 39.4). However, according to the Constitution, the prime minister and his cabinet are collectively responsible solely to the parliament (Articles 25.1.6 and 41.2). Also, given the more extensive powers of the legislative branch and, in particular, powers to remove the immunity of parliamentarians (Law on the Parliament 2020, Article 9.1), the speaker of the parliament effectively holds the second highest position. The speaker also replaces the president in case of absence, incapacity, or resignation. Therefore, the prime minister holds the third highest position.

The ideal design of the presidency was to mediate between conflicting parties and factions or be “above politics” (Chimid et al. 2016). Before the 2019 constitutional amendments, presidents could not afford to be non-partisan in the first term if they sought re-election. After these 2019 amendments, which raised the age of presidential candidates from 45 to 50 and limited them to one six-year term, the president’s incentives for “activism” during their time in office and role in the separation of power have considerably decreased. Currently, the president’s role as a counterbalancing power is minimal, and the most substantial power is veto power, which remains limited by the parliament’s ability to override it by two-thirds of its members.

In addition, before the 2019 constitutional amendments, the president played a prominent role in judicial nominations. Especially, the president could appoint all judges upon the proposal of the Judicial General Council (Article 51.2) and could appoint the prosecutor general and his deputies in consensus with the parliament (Article 56.2). After the 2019 amendments, the number of appointed judges is limited to five out of ten, and the rest are selected through open hearings (Article 49.5). Specifically, this amendment affected Article 49.5: Five members of the Judicial General Council (JGC) shall be selected from among the judges and openly nominate the other five members. They shall work once for four years, and a Chairman of the JGC shall be elected from among the members of the JGC. Reports on JGC activities in connection with ensuring the independence of judges shall be presented to the Supreme Court. The organization of the JGC, operational regulation, the requirements for its members, and the rules of appointment shall be determined by law. The Constitution remained ambivalent on who exactly is to make these appointments, leaving it to speculation that it most likely is the parliament. Nonetheless, new laws will presumably detail the nominations and appointments.

Constitutionally, the Supreme Court is the highest judicial body. The JGC is its administrative body. In cases of Supreme Court Justices, the JGC selects and nominates judges for an appointment either by the president or the parliament. The Constitution grants the Supreme Court authority to examine all lower court decisions and provide official interpretation of all laws except the Constitution. Articles 64.1 and 66 give the Constitutional Court the general power of constitutional interpretation. Nevertheless, given the appointment system, it is highly disputed whether the judiciary and the prosecutors can be truly independent in the existing system. Furthermore, in 2019, the Law on the Legal Status of Judges allowed the National Security Council consisting of the President, Prime Minister, and the Speaker of Parliament to remove judges (Transparency International 2019; Dierkes 2019).

5. Recent Constitutional Reform and Political Outcomes

In 2019, the government led by Mongolian People’s Party pushed comprehensive constitutional amendments that shifted the balance of power to the parliament and limited the presidential term. However, these changes did not go far enough in changing the nature of the political system, and it remained semi-presidential. After that, there were two other amendments. The amendment on August 25, 2022, repealed the limitations introduced by the 2019 amendments on the “double deel” issue.[3] The second amendment on May 31, 2023, introduced a mixed electoral system with 78 members of parliament elected by majoritarian and 48 by proportional representation.[4]

The 2022 repeal highlights the enduring importance of the “double deel” issue (“давхар дээл”, deel is the traditional Mongolian clothing). It is one of the most politicized legal issues centered on the debate whether cabinet members and members of parliament can hold concurrent posts. The initial Constitutional Court decision was that they could not, but the 1999/2000 amendment reversed it. Nonetheless, the 2019 amendments limited the number of such members of parliament to four, but the 2022 amendment removed this limitation. At the core of this issue is that members of parliament are granted political immunity (Article 29.2); therefore, leading to a higher risk of abuse of power, as cabinet members who are concurrently members of parliament have access to resources and immunity to evade justice. In the context of Mongolia with systemic corruption, this becomes a particularly controversial issue.

The 2023 amendment, though, is more about the enlargement of the legislature from 76 to 126 members. This amendment also introduced a mixed electoral system (78 majoritarian seats and 48 proportional seats) and was followed by corresponding changes in election laws. Since 1992, Mongolia has mostly had a majoritarian electoral system, and only had a mixed system for the 2012 parliamentary election (48 majoritarian seats and 28 proportional seats). The re-introduction of the proportional component also reversed the 2016 Constitutional Court ruling against it. As the process of adoption and the rationale behind this amendment was not open to public challenge or debate, it is likely to have been another instance of behind-the-door elite bargaining with a resulting compromise between politicians who are able to win concrete electoral districts and those who enjoy nationwide popularity and stand better chances on a national list.

The need for enlargement, though, is unlikely to have gained public support, and the official perspective is that it is all part of bringing ‘stability’ to the political system and ‘bringing parliamentarians closer to the people’ (Lkhaajav 2023). Earlier, the rationale for enlargement also included geopolitical considerations, such as reducing opportunities for external influence on a larger number of politicians and responding to a growing population (Bayarlkhagva 2022). Nonetheless, it is important to note that these changes do not address the main issues affecting the stability of the political system, such as low trust in political institutions and a weak party system. Tied to this is a lack of real opposition in the system that further reduces the accountability of the ruling party.

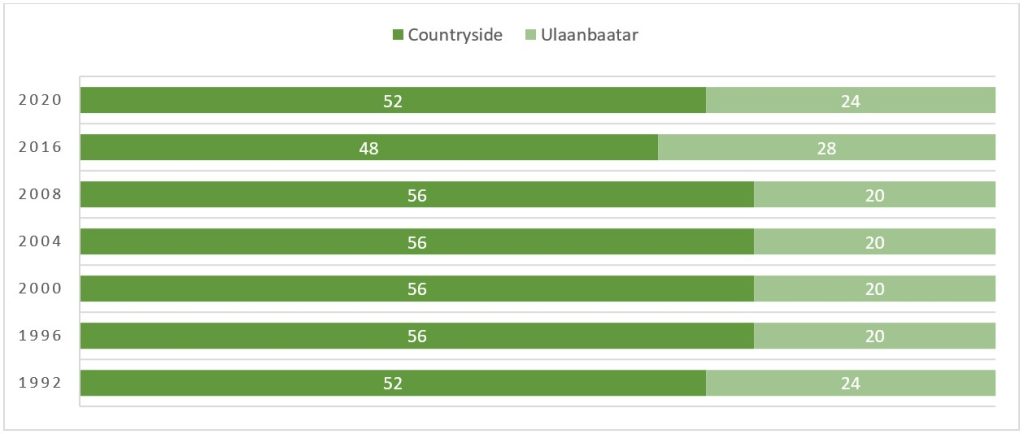

Given this, past research on the effects of electoral reform that compared the performance of electoral systems highlighted the continued importance of the urban/rural cleavage in Mongolia (Maškarinec 2018). It is yet to be seen how exactly the mandates are going to be distributed. However, considering that Ulaanbaatar continued to receive less than half of all the mandates despite having nearly half of the population, it is not certain that the existing population distribution is going to be considered. The main problem is the existing disbalance in mandates assigned for rural and urban representation. The reasons for the disproportion are mainly political as rural constituencies tend to vote for the ruling Mongolian People’s Party (MPP), and urban constituents tend to cast the most protest votes. In general, this has cast doubts on representativeness and equality of vote, but it has not been successfully challenged in the given power distribution.

Figure 5. Past Distribution of Mandates between Ulaanbaatar and the Rest of the Country

Source: General Election Commission of Mongolia

*Note: The 2012 election is excluded, as a mixed system was introduced at that time.

In the end, the main problem with the recent reforms is that they have been passed without offering an opportunity to challenge or dispute them. This invokes further concern about the state of accountability that the current political power setting has to offer. In the long term, a complete transition to parliamentarism has been a long-sought political goal by political elites. The prevalent belief is that stability in decision-making would result from a shift of power to parliament and the creation of a powerful prime minister position. Ambitious presidents mostly supported the transition to the presidential system. Nonetheless, one of the significant changes introduced by the 2019 constitutional amendments was a considerable change in the checks and balances system. The institutional equilibrium between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches shifted toward an all-powerful parliament and prime minister. It should not have been an issue; however, it happened in an environment with decreasing mechanisms of control needed to counterbalance or challenge misconduct.

6. Counterbalancing Misconduct

Due to the numerous laws passed in the last thirty years, there is a saying that Mongolian Law lasts three days. As a result, in comparison to the Constitution, the Law on Parliament and Law on Cabinet (1993) were amended dozens of times (at the time of writing, the count is 38+ times each), making it a highly contested area to interpret for lawyers or anyone for that matter. Some areas are ambivalent or untraceable after amendments because various political interests clash, and high-level politics is involved.

Regarding the constitutional procedures for removing prime ministers, a vote of no confidence has removed prime ministers at least three times.[5] Others managed to survive the vote of no confidence. As for presidential impeachments, no president has been removed while in office yet. N. Enkhbayar was arrested following his term in office and is the only former president that returned to party politics. Other former presidents retired from political life.

Nonetheless, the case of Kh. Battulga is also quite notable and shows struggles among the different branches. In particular, the changes from the 2019 constitutional amendment reduced the president’s power and granted more authority to the prime minister. One notable aspect was the introduction of a single six-year presidential term limit, sparking debates among politicians and legal experts regarding its immediate application to the current president. Thus, in 2021, following the Constitutional Court’s ruling that barred current and former presidents from running for re-election, President Kh. Battulga responded by issuing a decree to dissolve the ruling Mongolian People’s Party (MPP). He accused the MPP of influencing the court’s decision and of involvement in an NGO associated with retired military personnel, which he deemed inappropriate for political parties. Amidst rumors of political maneuvering such as cancelling meetings of the small chamber and changing one justice of the court by the Parliament, the Constitutional Court ruled against the re-election of current and former presidents.

In contrast, the parliament consists of 76 members, and after eight election cycles, there are many more parliamentarians to investigate. From the beginning, the most challenging obstacle for the prosecution was parliament immunity, guaranteed by the Constitution in Article 29.2 and legalized by Article 9.8 (formerly Article 34.7) in Law on the Parliament (May 07, 2020, version). Nevertheless, Article 9.1 states that the parliament shall decide whether to suspend the powers of a member of parliament. More specifically, in Article 9.1.1, when “the State Prosecutor General has submitted a proposal to the State Assembly to arrest him with evidence in the course of his criminal act or at the scene of the crime, and then to suspend his powers.”

Another legal challenge in 2016 to countering misconduct comes from the Law on State and Official Secrets. It is mainly criticized for shielding internal deal-making. While it was modified over the years, the changes were insubstantial, and the main challenges remained as its scope is defined too broadly (see Article 5 “Definitions” where almost anything is a “state secret”) and classification periods are long and easily extended (see Article 17 “Duration of information secrecy”).

In view of this, the existing checks and balances are such that high-level public officials rarely get prosecuted. The presence of public outrage and demonstrations is one of the deciding factors in bringing up high-profile cases. Among recent issues that received significant public attention was the dismissal of Speaker M. Enkhbold in 2019 after the public outcry over high-profile corruption scandals (Bittner 2019). Regarding the Constitutional Court, a notable high-profile case was the removal of its Chairman D. Odbayar, due to mounting public pressure over his involvement in the sexual harassment of a South Korean flight attendant on a flight from Ulaanbaatar to Incheon (IKON News Agency 2019-11-22). Most recently, the 2022 Coal Scandal brought down a number of politicians (including two members of parliament) after triggering a large-scale protest in Ulaanbaatar. There are other cases involving parliament members; however, many happened after their term in office or were eventually overturned. The main reason is that the judiciary can hardly maintain its political neutrality or independence under existing power arrangements.

7. Judicial Branch’s Independence

As previously stated, constitutionally, the Supreme Court has the authority to examine all lower court decisions and provide official interpretation of all laws except the Constitution (Article 50). The Constitutional Court holds the general power of constitutional interpretation (Articles 64.1 and 66). There is a debate among scholars and politicians about the need for a separate Constitutional Court when a Supreme Court could take over the duty of constitutional interpretation. After much back and forth in arguments, the most plausible clue to date comes from the composition of the Constitutional Court. While members of the Supreme Court are explicitly required to be professional lawyers (Article 51.3 “A Mongolian citizen who has reached thirty-five years of age with a higher education in law and a professional career of no less than ten years may be appointed as a judge of the Supreme Court”), the members of the Constitutional Court had to have high qualifications in politics and law (Article 65.2 “A member of the Constitutional Court shall be a Mongolian citizen who has reached forty years of age and has high qualifications in politics and law”), and their nominations applied the principle of the distribution of power between different branches. The Constitutional Court has nine members of the following distribution: the parliament, the president, and the Supreme Court respectively nominate three members each (Article 65).

Overall, the existing system of judicial nominations is one of the major barriers to judicial independence. The political nominations of justices and the prosecutor general introduce a high risk of politicization of the judiciary. The next big obstacle is the amendment to the Law on the Legal Status of Judges in 2019 that allows the National Security Council to remove judges (Transparency International 2019; Dierkes 2019). There are plausible arguments that it is necessary due to existing corruption in the legal system. The problem is that high-level corruption is endemic in the whole system, and the removal of judges can also serve political motives. Consequently, the issues with the judiciary’s political neutrality and independence undermine the judicial branch’s function as a counterbalance to the other branches of government.

From the beginning, the legacy of the socialist legal system impacted the judicial branch longer, as the reform in this branch was more gradual in comparison to the economic and pollical transformations in the 1990s. During the period of communism, the legal system was completely subordinate to the party state. After the establishment of democracy, the concept of division of power and the need to distance from one party rule led the reformers to adopt a constitution based on ideals of checks and balances. Thus, the introduction of an independent judiciary was a stated goal. Nonetheless, the external appointment system of major positions in the judiciary and prosecution politicized the branch. While political appointment of Supreme Court justices is a practice also present in other countries, the challenge in Mongolia is that the whole process of selection criteria is opaque and unchallenged, so appointments are often a behind the door compromise with loyalty as a main requirement.

8. Oversight Agencies and Their Capabilities

Mongolia has a longstanding problem with corruption in the public sector. Still, the main obstacle to legislation is not as much existence of loopholes and inconsistencies, but the issues summarized as the weak rule of law. According to Transparency International’s assessments, Mongolia’s 2021 corruption ranking stands at 110 out of 180 with a Corruption Perception Index of 35, which places it among countries with a serious corruption problem (Transparency International 2022).

The two major oversight agencies are the Mongolian National Audit Office and the Independent Authority Against Corruption of Mongolia (IAAC). The Mongolian National Audit Office is the country’s central audit institution. The Law on State Audit (2020) gives it a broad mandate. It states in Article 5.1. “The main goal of the state audit is to monitor the planning, distribution, use and spending of public finances, budgets and public property in a legal, economical, efficient and effective manner, as well as improving public financial management and supporting sustainable economic development.” In practice, though, it is limited in human resources and often runs into issues with overall capacity (ADB 2019). Unsurprisingly, when high-level politics is added, it is rare that a state audit finds any wrongdoings. The Constitution grants the parliament budgetary powers under Article 25.1.7. In response, Article 6.1 of the Law on State Audit gives the Mongolian National Audit Office the mandate to audit all except the parliament. Specifically, in the Law on State Audit, Article 6.5 states that it can audit the parliament “if requested by parliament.”

The IAAC is another oversight institution with an overly broad mandate that allows it to investigate corruption cases and educate the public about prevention mechanisms. According to the Law on Anti-Corruption (2006), the IAAC is in charge of income and asset declarations of the president, the prime minister and his cabinet, members of parliament, and officials appointed by them (Article 11.1.1). To date, the most significant obstacles to its capacity to actively investigate corruption cases of high-level public office holders are issues related to either political immunity or amnesty laws. As of July 2021, Mongolia has passed its seventh amnesty law (Baljmaa 2020). The problem is that some of these amnesty laws would apply to a broad range of cases that would also grant protection from prosecution for corruption or lead to the termination of cases under investigation by the IAAC (UNCAC Coalition 2015). Generally, the IAAC faces frequent accusations of operating at random or with significant political bias. In the past, the president could appoint the head of the IAAC, but in January 2021, the parliament made amendments to the Law on Anti-Corruption that shifted this power to the prime minister (Article 21, updated; Baljmaa 2020). This shift can be seen as further empowering the prime minister’s position.

These institutional factors contribute to the deterioration of proper checks and balances in the system and explain why so much of the high-level corruption tends to go undetected or under-investigated.

9. Prospects

Following the development of media headlines in recent years, analysts and commentators have started describing Mongolian political developments as a crisis of democracy. While multiple problems contribute to the overall decline in democratic governance, the core issue described in this report is that there are currently no efficient systems of control to form proper checks and balances. The past equilibrium of checks and balances has been broken, but the new system is highly unbalanced. As noted earlier, the shift of power to the legislative branch should not have been a problem, but it happened in the context of a weak party system and a weak judicial system.

Overall, this leads to the conclusion that despite the constitutional design and intent, the principle of separation of power runs into considerable challenges. Moreover, it is increasingly difficult to enforce in the current political setting, as other branches and oversight agencies cannot adequately check legislative power. As a result, this leads to rather grim prospects for horizontal accountability in the short term. As for the medium to long term, it is still too early to judge, as this type of power arrangement is unstable and there are talks about further reforms. Despite the political elite’s insistence that the reforms were made in order to ensure political stability, there are more factors to consider. One of the underlying convictions of the political elites is that the fast turnover of the government undermines political stability; as a result, all recent major reforms focused on solidifying the legislative power and the prime minister with his cabinet. In reality, the government turnover should not have been a problem, but the fast turnover of the civil and public servants in the corresponding institutions was a problem for policymaking and implementation.

It was earlier noted that if there is an erosion of horizontal accountability, then the quality of democracy will deteriorate (Sato et al. 2022). Also, for domestic politics, it is important to mention that cross-national research shows that dominant party regimes are found to be more vulnerable to mass protests (Ulfelder 2005). Moreover, the current regional instability is likely to lead to further economic decline, which means even less resources for reform and higher stakes in losing political power. Altogether, leading to more uncertainty and risk externally and domestically.

The big picture is that since Mongolia started its democratization in 1989, its democratic performance has been relatively high among the Third Wave of democracies. Especially, when we consider that Soviet institutional legacy and levels of economic development make it analytically closer to post-Soviet Central Asian states. Yet, if we consider the developments since 1992 (when democracy was institutionalized by the Constitution), by now we still can also observe gradual decline in the quality of its democracy.

However, despite these challenges, the political elite is likely to remain interested in the democratic system. Mongolian geopolitical position makes its democracy vulnerable to institutional spillover effects from China and Russia. Yet, its foreign policy of attracting third neighbors makes the political elites interested in maintaining the democratic system. This foreign policy has been a cornerstone of Mongolian foreign affairs, and fundamentally it tries to balance Mongolia’s dependence on China and Russia by finding other partners. Implicitly, it also had a lasting impact on its choice of political system as it supported Mongolia’s membership in the community of democracies. Nonetheless, due to the existing problems with systemic corruption, the political elite is not interested in strengthening the judiciary’s role and the rule of law, which are crucial for advancing democratic quality in Mongolia. In view of 2024 parliamentary elections that would involve a much larger legislature, it is yet to be seen in the future whether this would indeed ensure political stability and increase efficiency.

10. Solutions

Given the current power arrangements, how do we enhance horizontal accountability?

The World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, which ranges from 0 to 1, gives Mongolia an overall score of 0.54, which indicates a ‘mediocre’ performance (World Justice Project 2022). Globally, it is ranked 65 among the 128 countries, and regionally its overall performance is the closest to Indonesia. Among the main factors included in this indicator is that it scores the lowest in terms of the absence of corruption in government. If we delve deeper into subfactors, we can see that it has one of the worst performances in the use of office for private gain by legislative branch public officials. As of 2020, it was ranked 114 out of 128 countries, which places it among the worst performers globally and regionally.

This report described the current constitutional setting and the imbalance in power arrangements that were introduced by the amendments. One of the main risks in the current political setting is the overconcentration of power in the legislature, which any existing institutional controls cannot adequately counterbalance. Importantly, the shifts of power happened at a time when there was one party dominance, weak counterbalancing institutions, and most importantly, a lack of judicial independence. Altogether this leads to a political environment where public officials in power are barely accountable. The main concern is that it also leads to decreasing transparency of decision-making in the legislature with very little oversight or chance of being challenged by any other institutions.

Thus, the main solution should be focused on strengthening and improving the judicial branch. At the time when most of the counterbalancing institutions are weak, that remains the general approach. That is given the view that the power imbalance among different branches is especially relevant for the judicial branch, as judicial nominations and budgetary constraints put it at a high risk of manipulation by the other branches of the government.

While judicial reform has been on the agenda throughout Mongolia’s democratization process, earlier efforts of the top-down or institution-building approach for judicial reform have been unsuccessful (Fenwick 2001; White 2009; Chimid 2017). The problem remains unresolved to date, as at a deeper level, such approaches do not work well in countries with systemic corruption, where the key stakeholders are both reformers and the reformed.

As a persistent problem, it was attributed to the fact that institutions involved in the judicial reforms had ignored the core problems, such as the corruption of the judicial branch (White 2009). In addition, while there is a lot of focus on political independence, the problems are also related to judicial budget, integrity, transparency, and accountability. In the end, this suggests that in the current institutional setting in Mongolia, the mixed approach with bottom-up pressure for reform and implementation is more appropriate.

Other general solutions are that Mongolia needs to continue developing its party system. Currently, the weakness of the party system is contributing to the lack of opposition as a balancing force in the democratic system. In particular, to counter special interests the opposition should play an important role in directing agencies charged with preventing and investigating corruption (O’Donnell 1998). It is highly unlikely that within the existing power concentration, there is the political will to give the preventative agencies or oversight agencies the actual capacity to ensure justice. To date, the overconcentration of power and decreasing accountability only increased the risk that decision-making is not made in the wider interests of society.

Finally, government accountability is a multi-actor and a multi-dimensional process. Therefore, in addition to the improvements in the extent of horizontal accountability, government’s accountability to its citizens (vertical accountability) and media and civil society (diagonal accountability) needs to improve. As part of the comprehensive approach leading to improvements and transparency in governance, the bottom-up pressure would involve increased activity on behalf of the media and various civil society organizations that ensure diagonal accountability. As for vertical accountability, the vigilance of public opinion influencers and citizens is increasingly important as well. These two aspects of accountability, though, would be a topic of future research.

We would like to note that the concept of ‘checks and balances’ is still rather new in Mongolia. Historically there was no precedent, and during communist times the centralizing and all-encompassing control of the party did not even allow for any balancing forces to exist. Thus, it is an accomplishment of the modern democratic system to introduce the concept and the related condition of ‘accountability’. Even so, it remains an obscure concept to the general population and even to some of the older cohort of politicians. The most common Mongolian translation of accountability is ‘хариуцлага’, which does not properly convey its meaning within a democratic setting. The main issue is that the direct translation of ‘хариуцлага’ is ‘responsibility’, which unnecessarily loaded the concept with a paternalistic undertone. Moreover, the principles of separation of power are also not intuitive for those unfamiliar with the framework of democratic governance. Thus, from the beginning, to an average person, it can lead to an incorrect mindset and expectations about the direction and types of accountabilities in power relations.

Nevertheless, the accomplishment of the democratic system is that issues such as the types of accountabilities and their needs are receiving attention. It is thus important for the future development of the Mongolian democracy to continue such discussions and try to resolve them as they emerge. At the end of the day, Mongolian democracy is still relatively young and would require more adjustments and improvements. Most importantly, though, these changes would require all stakeholders to participate openly and transparently, as a stable democracy needs not only active but informed voters.

11. Conclusion

We can conclude that while prospects for increasing horizontal accountability of the government are not good in the short term, the system still has the capacity for improvement. There are several major factors challenging the proper functioning of checks and balances in the system that need to be continuously addressed. Importantly, there is a lack of judicial independence. In the existing system, the key judiciary members are most likely to be political appointees; as a result, their political neutrality and independence are questionable. Relatedly, it becomes a further issue when dealing with cases that involve the high office. The extent of judicial reform in the past was hindered by mostly the top-down approach taken by the donor agencies. In the future, a mixed approach, including bottom-up pressure from the citizens and the community, could be a better approach for ensuring that Mongolian democracy continues to evolve positively and to ensure the rule of law. In addition, more transparency in decision-making is necessary to ensure that the legislation is not just passed but checked. For this, the role of diagonal accountability needs to improve, which, at a minimum, would involve improved media access and coverage.

A further issue of concern pointed out in this report is that the major oversight agencies, such as the National Audit and the IAAC, are not free from political interference. As for other avenues, there is a lack of support and opportunities to involve citizen oversight agencies. Overall, these challenges create considerable gaps in horizontal accountability in the system. While not evident and difficult to assess in the short run, a lot of these institutional challenges have a cumulative impact on the quality of democracy.

It is not an overstatement to suggest that unless the institutional ways of directing public concerns are improved, the instances of mass protest might only increase in the existing political environment. In particular, the long-term institutional advantages of the ruling party and the current weakness of the opposition have also led to a system with one-party dominance, which is prone to protest. While protesting is not necessarily a threat and can be a political outlet in a democracy, the issue is that the government’s response to the public protest was mostly superficial and later focused on limiting rather than addressing protesters’ concerns. Over time, the risk of taking this approach is that unless the underlying governance issues, particularly institutional ways to defend and represent the public interest are not improved, the confrontation between the government and the public might become more serious. Nevertheless, in the short term, given all the benefits of the status quo, it is unlikely that the current political elite would push and implement the necessary reforms, leaving citizens’ vigilance and participation as the primary tools leading to policy change. ■

References

Asian Development Bank: ADB. 2019. “Mongolia: Strengthening the Supreme Audit Function.” ADB Technical Assistance Report. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents/52285/52285-001-tar-en.pdf

Baljmaa T. 2020. “Law on Anti-Corruption Amended.” MONTSAME News Agency. December 31. https://montsame.mn/en/read/248530

———. 2021. “Mongolia Adopts Seventh Amnesty Law.” MONTSAME News Agency. July 5. https://montsame.mn/en/read/269044

Bayarlkhagva, Munkhnaran. 2022. ‘New Constitutional Amendments in Mongolia: Real Reform or Political Opportunism?’ The Diplomat, July 1. https://thediplomat.com/2022/07/new-constitutional-amendments-in-mongolia-real-reform-or-political-opportunism/

Bittner, Peter. 2019. “Mongolia’s Crisis of Democracy Continues.” The Diplomat. January 31. https://thediplomat.com/2019/01/mongolias-crisis-of-democracy-continues/

Chimid, Enkhbaatar. 2017. ‘The Development of Judicial Independence and the Birth of Administrative Review in Mongolia’. Academia Sinica Law Journal, Comparative Administrative Law in Asia, no. 21 (September): 155–219.

Chimid, Enhbaatar, Tom Ginsburg, Amarjargal Peljid, Batchimeg Migeddorj, Davaadulam Tsegmed, Munkhsaikhan Odonkhuu, and Solongo Damdinsuren. 2016. “Assessment of the Performance of the 1992 Constitution of Mongolia.” United Nations Development Programme. https://www.undp.org/mongolia/publications/assessment-performance-1992-constitution-mongolia

Dierkes, Julian. 2019. “The Beginning of the End of Democracy?” Mongolia Focus (blog). March 27. https://blogs.ubc.ca/mongolia/2019/judicial-appointments-national-security-council/

Elkins, Zachary and Tom Ginsburg. 2022 “Characteristics of National Constitutions, Version 4.0.” Comparative Constitutions Project. Last modified: October 24. comparativeconstitutionsproject.org

Fenwick, Stewart. 2001. ‘The Rule of Law in Mongolia: Constitutional Court and Conspiratorial Parliament.’ Australian Journal of Asian Law 3, 3: 213–235.

Fish, Steven Michael. 1998. “Mongolia: Democracy Without Prerequisites.” Journal of Democracy 9, 3: 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1998.0044

______. 2001. “The Inner Asian Anomaly: Mongolia’s Democratization in Comparative Perspective.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 34, 3: 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-067X(01)00011-3

‘General Election Commission of Mongolia’. n.d. Accessed 31 July 2023. https://gec.gov.mn/

IKON News Agency. 2019. “Chairman of Tsets D. Odbayar Was Dismissed from His Post [Цэцийн Дарга Д.Одбаярыг Албан Тушаалаас Нь Чөлөөллөө].” November 22. https://ikon.mn/n/1qba

Law on Anti-Corruption [Авлигын эсрэг хууль] (2006). https://legalinfo.mn/

Law on State Audit [Төрийн аудитын хууль] (2020). https://legalinfo.mn/

Law on the Cabinet [Засгийн газрын тухай хууль] (1993). https://legalinfo.mn/

Law on the Legal Status of Judges [Шүүгчийн эрх зүйн байдлын тухай хууль] (2019). https://legalinfo.mn/

Law on the Parliament [Их Хурлын тухай хууль] (2020). https://legalinfo.mn/

Law on State and Official Secrets [Төрийн болон албаны нууцын тухай хууль] (2016). https://legalinfo.mn/

Lkhaajav, Bolor. 2023. ‘Mongolia’s Constitutional Reform Enlarges Parliament, Advances a Mixed Electoral System’. The Diplomat. June 2. https://thediplomat.com/2023/06/mongolias-constitutional-reform-enlarges-parliament-advances-a-mixed-electoral-system/

Lührmann, Anna, Kyle L. Marquardt, and Valeriya Mechkova. 2020. ‘Constraining Governments: New Indices of Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal Accountability’. American Political Science Review 114, 3: 811–820. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000222

Maškarinec, Pavel. 2018. ‘The 2016 Electoral Reform in Mongolia: From Mixed System and Multiparty Competition to FPTP and One-Party Dominance’. Journal of Asian and African Studies 53, 4: 511–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909617698841

O’Donnell, Guillermo A. 1998. ‘Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies’. Journal of Democracy 9, 3: 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1998.0051

Sanders, Alan J. K. 1992. “Mongolia’s New Constitution: Blueprint for Democracy.” Asian Survey 32, 6: 506–520. https://doi.org/10.2307/2645157

Sant Maral Foundation. 2023. “Politbarometer #22.” https://www.santmaral.org/publications

Sato, Yuko, Martin Lundstedt, Kelly Morrison, Vanessa A. Boese, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2022. “Institutional Order in Episodes of Autocratization.” V-Dem Working Paper 133. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4239798

The Constitution of Mongolia (1992). https://legalinfo.mn/

Transparency International. 2019. “Rule of Law and Independence of Judiciary Under Threat in Mongolia.” July 4. https://www.transparency.org/en/press/rule-of-law-and-independence-of-judiciary-under-threat-in-mongolia

______. 2022. “2021 Corruption Perceptions Index – Explore the Results.” January 25. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021

Ulfelder, Jay. 2005. “Contentious Collective Action and the Breakdown of Authoritarian Regimes.” International Political Science Review 26, 3: 311–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512105053786

UNCAC Coalition. 2015. “International Organisations Call on Mongolian Parliament to Withdraw Corruption Amnesty Law.” October 8. https://uncaccoalition.org/international-organisations-call-on-mongolian-parliament-to-withdraw-corruption-amnesty-law/

V-Dem Project. 2022. “V-Dem Dataset V12.” https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds22

White, Brent T. 2009. ‘Rotten to the Core: Project Capture and the Failure of Judicial Reform in Mongolia’. East Asia Law Review 4: 209–275.

World Justice Project. 2022. “Rule of Law Index – Mongolia.” https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/country/2020/Mongolia

[1] Chairman of Board, Academy of Political Education

[2] Senior Researcher, Sant Maral Foundation

[3] See the document at https://legalinfo.mn/mn/detail?lawId=367&type=2 (in Mongolian).

[4] See the document at https://legalinfo.mn/mn/detail?lawId=16759482929681&showType=1 (in Mongolian).

[5] The exact number is difficult to trace, due to the absence of open information on the topic.