![]()

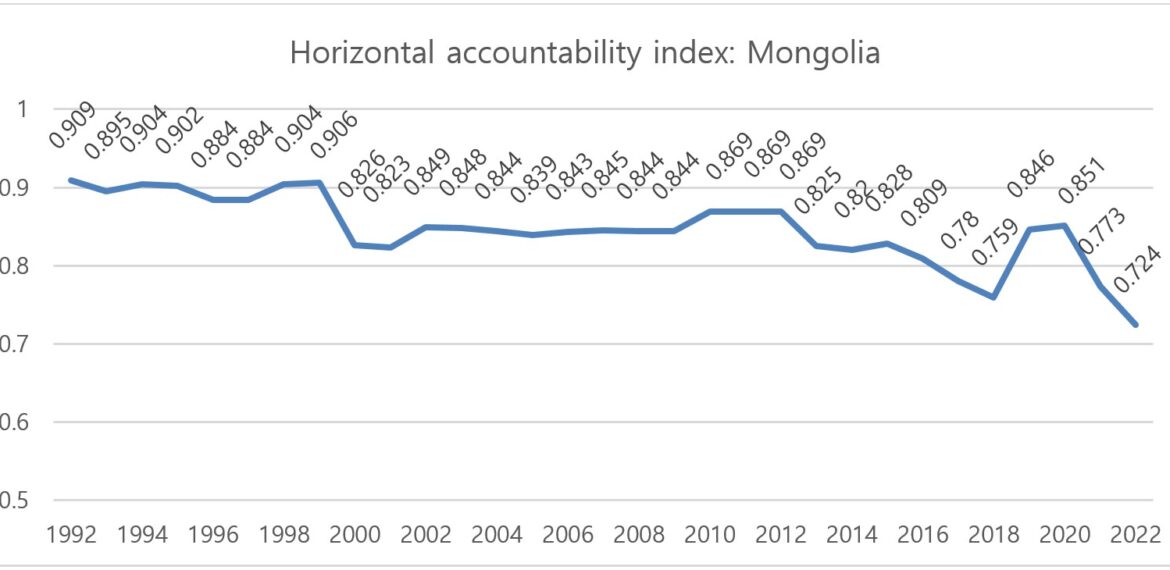

The Horizontal Accountability Index from V-Dem provides an empirical metric to measure the extent to which state entities in a country can hold one another accountable. Analyzing the data for Mongolia from 1990 to 2022 reveals interesting trends and fluctuations that offer insights into the country’s evolving governance structure and democratic practices.

Figure 1. V-Dem Horizontal Accountability Index: Mongolia 1992-2022

Source: V-Dem 2023

• Initial Surge (1990-1992): Beginning with a score of 0.686 in 1990, there is a sharp rise to 0.909 in 1992. This period corresponds with Mongolia’s shift towards democracy, and the spike suggests rapid institutional reforms aimed at introducing checks and balances.

• Stability and Marginal Fluctuations (1993-1999): Post the initial surge, the index stabilizes in the high 0.8 to low 0.9 range. This period reflects a consolidation phase, with Mongolia striving to maintain a balance of power among its state institutions.

• Decline at the Turn of the Century (2000-2005): Starting in 2000 was a noticeable dip, which reached a low of 0.839 in 2005. This downward trajectory could indicate challenges in sustaining institutional checks, possibly due to political or economic factors.

• Relative Stability with Mild Resurgence (2006-2012): The period sees the index oscillating in the mid-0.8 range with a slight rise to 0.869 by 2012, suggesting efforts to re-strengthen horizontal accountability mechanisms.

• Dips and Peaks (2013-2020): This period is marked by significant fluctuations, from a dip to 0.825 in 2013 to a resurgence in 2019-2020. Such fluctuations indicate political changes and institutional reforms impacting the balance of power.

• Recent Decline (2021-2022): A concerning decline has been observed in the last two years, with the index dropping to 0.724 in 2022, the lowest in the dataset. This drop suggests recent challenges or setbacks in ensuring horizontal accountability.

Over three decades, Mongolia’s Horizontal Accountability Index has seen notable shifts. While the 1990s reflected a promising start in institutionalizing checks and balances, subsequent years presented a mix of challenges and recoveries. The most recent decline signals a potential need for a renewed emphasis on bolstering mechanisms that ensure state entities remain accountable to one another. Analyzing whether these trends and the varying public trust in institutions central to horizontal accountability—especially in terms of how the judiciary and oversight bodies address corruption scandals—would be insightful.

3.1. Public Trust in Institutions

While public perceptions don’t directly measure the judiciary’s capacity to hold the executive accountable, they can, especially when grounded in tangible events, offer valuable insights into its performance. The implications of these high-profile corruption scandals and the delayed and unclear court decisions have resulted in public distrust in the court. However, distrust in the judicial system has been high since the democratic transition more than three decades ago.

• According to a 1994 survey conducted by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and the Academy of Sciences, court was the second most corrupt institution at soum levels (Mont 2002).

• In 2005, a public opinion survey conducted as part of the ‘Judicial Reform Program’ found that 90 percent of the respondents believed court decisions favor wealthier and more influential individuals over ordinary ones (Чимид 2006, p. 157).

• In 2008, the Open Society Foundation surveyed professionals in the judicial system and found that 54 percent of the participants believed ‘conditions for impartiality and independence are not met in Mongolia’ (White 2008, p. 15). To the statement ‘interference of other organs of the state and politicians is high,’ 42 percent agreed and 38 percent said not sure. The research also collected anecdotal evidence from anonymous judges on how prominent political figures directly attempted to interfere in their decisions.

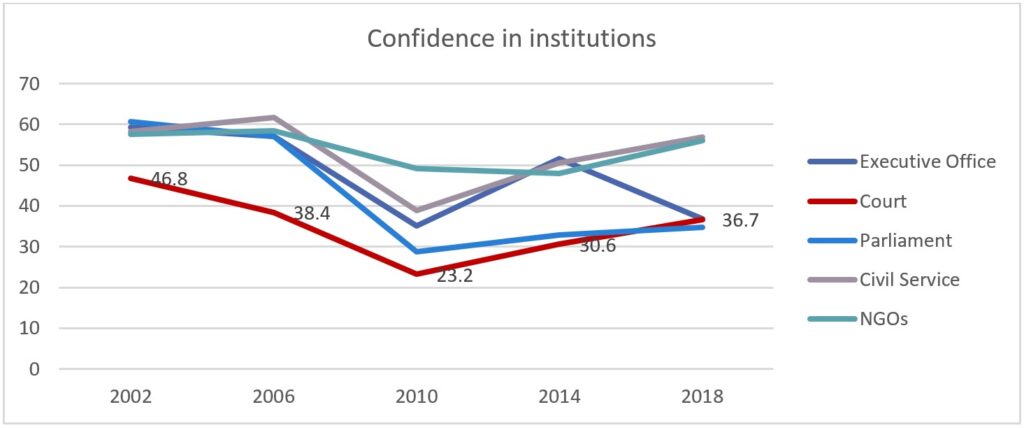

• The Asian Barometer Survey in 2018 found that the proportion of respondents saying they trust the Courts was 36.7%, slightly higher than trust in parliament (34.7%) and much lower than trust in the president and prime minister (68.0%). Figure 2 shows that trust in the courts has been lower than in other institutions (Asian Barometer Survey).

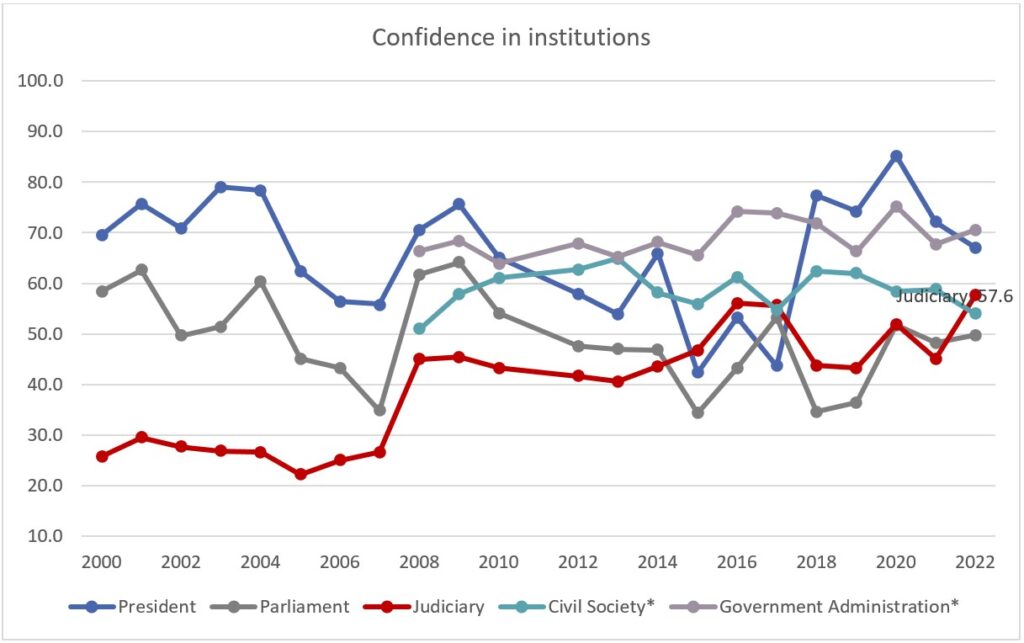

• As the Sant Maral Foundation’s public opinion surveys between 2007 and 2022 show, the proportion of respondents indicating trust in the courts is higher than those reported in the Asian Barometer Survey mentioned above. However, a similar trend of lower levels of trust in the courts compared to other institutions is observable.

Figure 2. Proportion of respondents answering ‘trust or trust a lot’ in different institutions, ABS 2002-2018

Source: Asian Barometer Survey, author’s calculation

Figure 3. Confidence in institutions 2000-2022

Source: Sant Maral Foundation, 1992-2022