![]()

Reports | Jul 3, 2024

Mina Sumaadii

Senior Researcher, Sant Maral Foundation

Ganbat Damba

Chairman of Board, Academy of Political Education

Editor’s Note

Mina Sumaadii, Senior Researcher at the Sant Maral Foundation, and Ganbat Damba, Chairman of Board at the Academy of Political Education, examine Mongolia’s democratic challenges, including the lack of government accountability, weak enforcement of legislation, and restricted media freedom. The majoritarian election system, coupled with the laws granting the government broad control over freedom of expression, has resulted in a one-party dominant system. Sumaadii and Damba argue that without addressing systematic corruption and institutional weaknesses, citizen protests become the only viable form of political expression, as elections have failed to establish a balanced multi-party system.

1. Introduction: The State of Accountability of Mongolia

In this series of reports on accountability, three types of accountability will be examined: government accountability to its citizens (vertical accountability), government responsibility to other institutions (horizontal accountability), and government accountability to the media and civil society groups (diagonal accountability). This report examines vertical accountability in the Mongolian political system. Existing research considers that in a system with vertical accountability, citizens can hold their government accountable through elections and political parties (Lührmann 2020, p. 813).

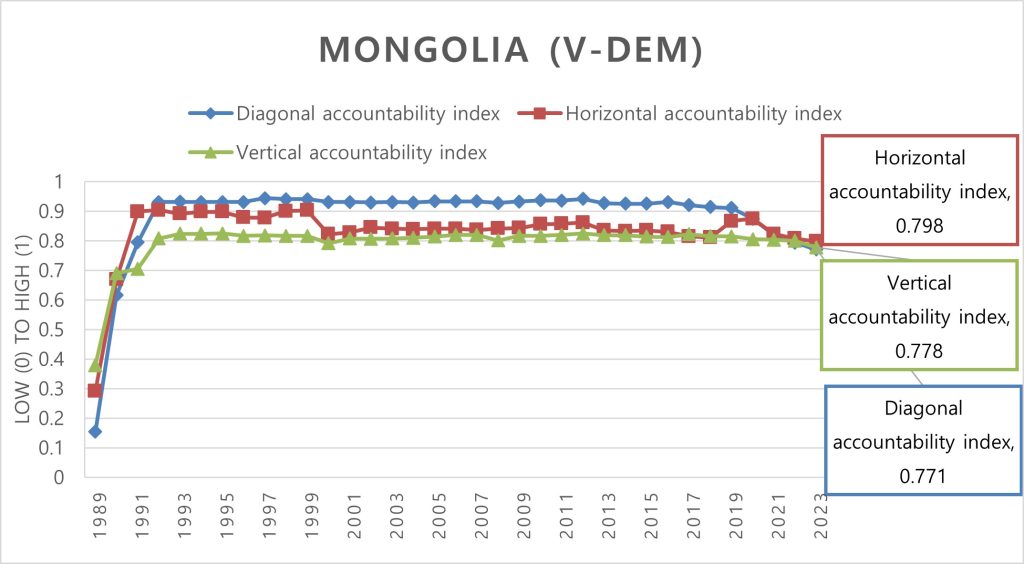

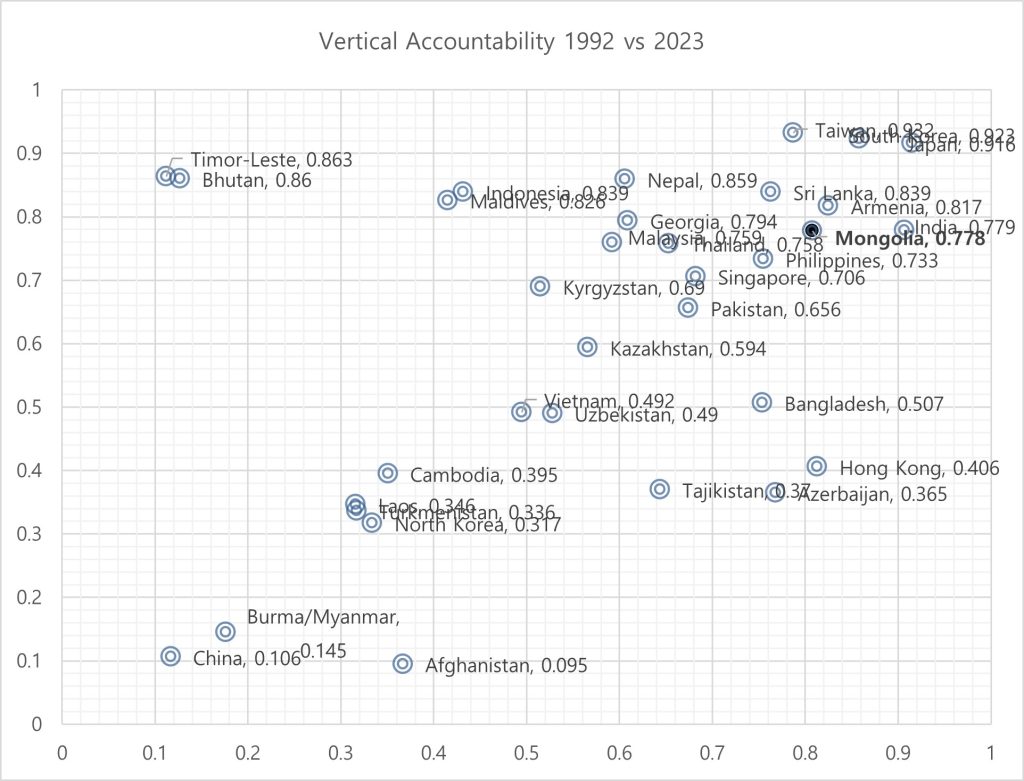

The most important change is that the latest “Democracy Report 2024” placed Mongolia in the democratic “gray zone” between “electoral democracy” and “electoral autocracy.” From 1992 to 2022, Mongolian performance in V-Dem Projects accountability indices was consistently classified as an “electoral democracy.” On average, it scores relatively high in vertical and diagonal accountability indices, but its performance in horizontal accountability is in decline (Figure 1). Since the institutionalization of democracy with the 1992 constitution, its vertical accountability performance and subsequent decline make the case most similar to India (Figure 2).

Figure 1. V-Dem Accountability Indices: 1989 to 2023

Source: Data obtained from V-Dem Project

Figure 2. V-Dem Vertical Accountability Asia: 1992 vs. 2023

Source: Data obtained from V-Dem Project

In general, these scores describe a system where elections result in the transfer of power, but there are flaws in governance. In the case of Mongolia, these flaws are related to (1) poor government accountability, (2) poor enforcement of legislation that is part of institutional control mechanisms and increasingly (3) freedom of the media. Over the years, the main challenge to analyzing and evaluating government performance and policies was the lack of transparency in decision-making and a lack of access to administrative information. Moreover, most of the significant legislation introduced in the past few years was introduced hastily with little challenge by the opposition or public oversight, which is required by the legislative process.

Consecutive constitutional amendments, starting from the significant amendments in 2019, followed by a further amendment on August 25, 2022, and culminating in the 31 May 2023 amendment, introduced a mixed electoral system with 78 members of parliament elected by majoritarian and 48 by proportional representation. The landmark cyber security law (2021) and human rights laws also received minimal scrutiny and were passed without public discussion. Moreover, only the president’s veto stopped controversial social media laws that the Mongolian parliament passed after a considerable public outcry (Buyanjargal 2023; Ooluun 2023). There was also condemnation from the civil society groups and the international community (CIVICUS Monitor 2023; Jamgansuren 2023; Dulamkhorloo Baatar 2023). These laws granted the government broad control over online content, including censorship of discussions about officials and the ability to shut down the internet. Legally, in cases of such procedural breech, the Constitutional Court of Mongolia can challenge the adopted legislation(On the Proceedings of Disputes in the Constitutional Court [Үндсэн Хуулийн Цэцэд Маргаан Хянан Шийдвэрлэх Ажиллагааны Тухай] 1995). Yet, the Constitutional Court is a highly politicized institution; thus, so far, no challenges to this legislation have been issued. Nonetheless, in the case of the social media laws, the presidential veto was supported by 89 percent of the parliamentarians, and the bill was rejected (RSF 2023a).

Another recent development is that small parties without a seat in parliament opposed the new electoral laws that decreased the number of electoral districts from 29 to 13 enlarged regional constituencies. Such large electoral districts are known to benefit large parties with extensive resources and networks in the rural areas, putting small parties and independent candidates at a considerable disadvantage in the 2024 parliamentary elections. The media reports that the Constitutional Court is “considering” whether to take on the case (Uyan 2024; Nomin 2024). The result of their decision would further highlight whether the government is planning to uphold inclusivity as part of its commitment to a democratic electoral process. Notably, the 2024 electoral system’s majoritarian seat distribution gave the urban constituencies only 24 mandates out of 78, further reducing their chances (Ulaanbaatar News 2023). Moreover, it is yet to be specified how the proportional candidate lists would accommodate and represent them.

Given this, the disregard for transparency in legislative procedure and public scrutiny, together with the overall deterioration in horizontal accountability, invoke concerns. As evident from the adoption of recent legislation, the government continuously excluded stakeholders and undermined freedom of speech. Findings from cross-national research show that the erosion of horizontal accountability is related to the deterioration in the quality of democracy (Sato et al. 2022).

Given this gap, the two sides of vertical accountability in Mongolia will be analyzed: (1) the government’s side through its organization of elections and the political party landscape, and (2) the public’s side through the perception of government performance and accountability. This report will investigate vertical accountability since citizens’ vigilance is one of the last bastions of resistance to the processes set by the government.

2. Electoral Accountability and Declining Party Competition

2.1. Elections and Political Party Landscape

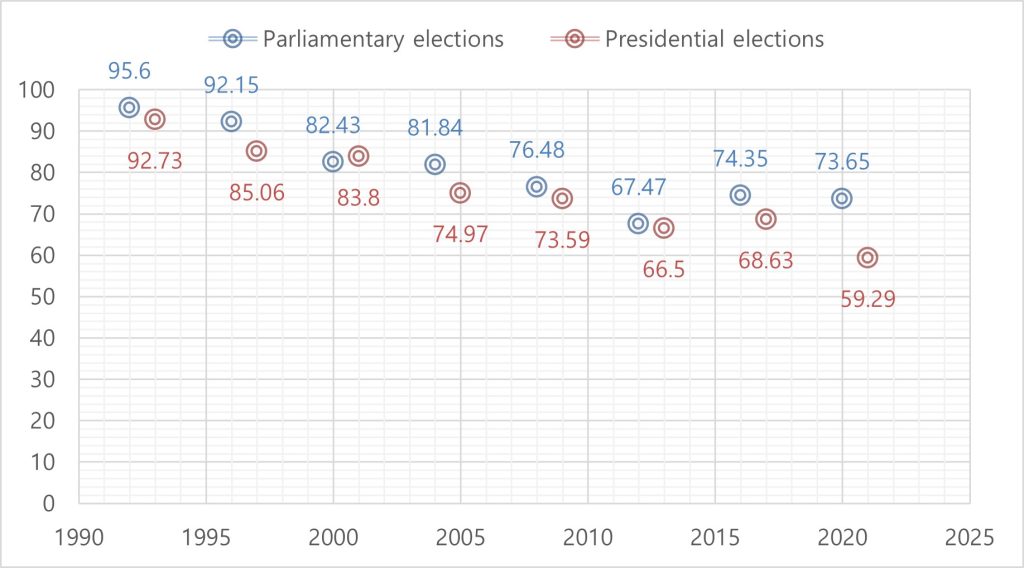

After the 1992 Constitution institutionalized democracy in Mongolia, the voter turnout was relatively high in most elections, but still, we can observe a gradual decline in voter participation (Figure 3). It was very high in the 1990s, mainly due to the novelty effects, but then, similar to other democracies, the enthusiasm decreased over time. Nevertheless, it remains high for parliamentary elections and is mainly decreasing for the presidential elections, highlighting the greater weight of parliament in the political system. The COVID-19 restrictions can explain the low turnout for the most recent 2021 presidential election. Nevertheless, it will be seen in the June 2024 parliamentary elections that the participation of two-thirds of the electorate became the new norm.

Figure 3. Voter Turnout in Parliamentary and Presidential Elections since 1992

Source: Data from the General Election Committee of Mongolia

Another main development is that the mostly majoritarian system led to the dominance of two parties, as smaller parties were unable to compete outside of the capital. The challenges for smaller parties, newcomers, and women were primarily due to resources that became increasingly relevant to running campaigns, establishing and maintaining rural networks, and covering large electoral districts. In rural areas, the poorly developed infrastructure, geographic size, and scattered population required considerable funds for campaigning. Therefore, except for the two main parties, there was rarely any other political representation visible outside of Ulaanbaatar. The Mongolian People’s Party (successor to the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party) and the Democratic Party (successor of the Democratic Union Coalition) are considered the main political forces. However, the future of DP is uncertain, as it still cannot recover from the defeat in the past two elections, and opinion poll results are unfavorable.

Table 1. Electoral System: 1992 to 2024

| Elections | Electoral System | Number of Constituencies | Number of Seats | Mandates | MPRP/MPP | DUC/DP | |||

| Rural | Urban | % Votes | % Seats | % Votes | % Seats | ||||

| 2024 | Mixed* | 13+1 | 78+48 | 54+* | 24+* | – | – | – | – |

| 2020 | Majoritarian | 29 | 76 | 52 | 24 | 49.3 | 81.6 | 24.5 | 14.5 |

| 2016 | Majoritarian | 76 | 76 | 48 | 28 | 46.5 | 85.5 | 34.2 | 11.8 |

| 2012 | Mixed* | 26+1 | 48+28 | * | * | 33.5 | 35.4 | 34.2 | 52.1 |

| 2008 | Majoritarian | 26 | 76 | 56 | 20 | 43.0 | 59.2 | 39.2 | 36.8 |

| 2004 | Majoritarian | 76 | 76 | 56 | 20 | 48.8 | 47.4 | 44.8 | 44.7 |

| 2000 | Majoritarian | 76 | 76 | 56 | 20 | 51.5 | 94.7 | 24.1 | 1.3 |

| 1996 | Majoritarian | 76 | 76 | 56 | 20 | 45.7 | 65.8 | 39.9 | 32.9 |

| 1992 | Majoritarian | 26 | 76 | 52 | 24 | 57.1 | 92.1 | 31.3 | 6.6 |

Source: Data from the General Election Committee of Mongolia

*Note: The 2012 and 2024 electoral systems are mixed (majoritarian and proportional), where the proportional part is based on a nationwide candidate list. This makes the allocation of rural vs urban number of mandates not directly applicable. Still, at the time of writing the exact structure and procedures for the proportional element of the upcoming 2024 parliamentary election has not been specified.

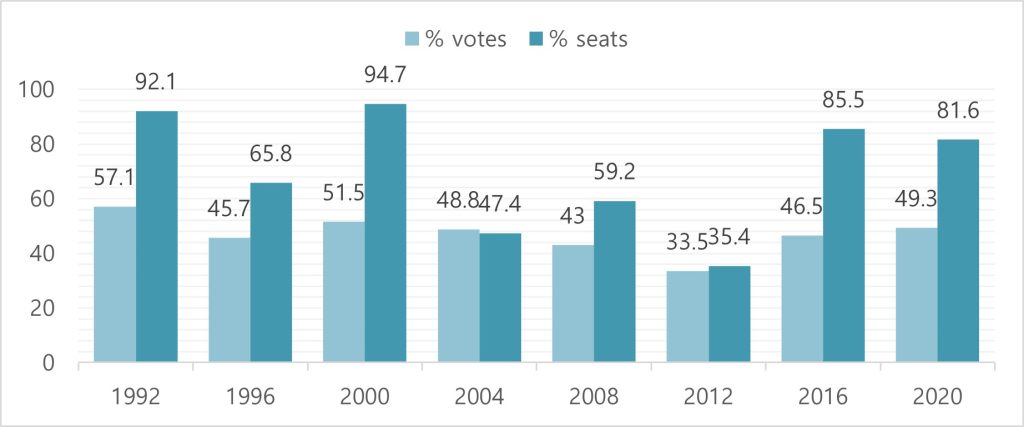

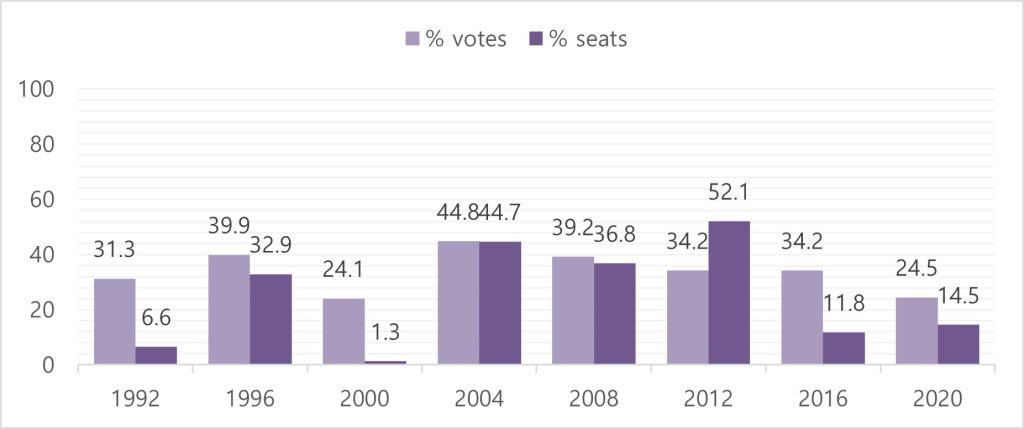

From Table 1, we can see that based on the performance of the two main parties in the past elections, the relationship between the total votes cast and the number of seats obtained is not proportional. The type of electoral system, the number (directly related to size) of constituencies, and, more recently, gerrymandering led to distortions. In some of the elections, those discrepancies were considerable (See Figures 4 and 5), which was also reflected in the increasing criticism of the electoral system. There was also the role of urban and rural cleavages and the related distribution of Ulaanbaatar and rural area mandates. Historically, the rural constituencies favored the MPRP/MPP. Thus, the high number of rural mandates in the rural area mostly benefited the ruling party.

Figure 4. MPRP and MPP Votes and Seats

Figure 5. DUC and DP Votes and Seats

Source: Data from the General Election Committee of Mongolia

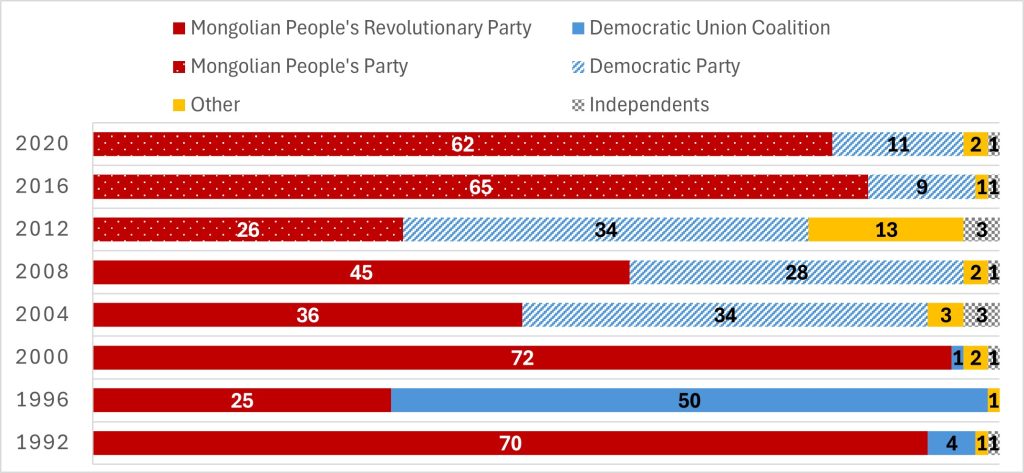

At the same time, party registration was rarely a problem, and to date, dozens of parties emerged right before the elections just to disappear shortly afterward. As noted earlier, for smaller parties, the main challenge was the lack of resources, which continuously disadvantaged them in the rural areas and made them unable to compete with larger parties. The size of electoral districts and a lack of established rural networks were a main challenge they could not overcome. This was the same for independent candidates, newcomers, and women, who lacked main party affiliation and support. After the 2016 defeat of one of the main parties — the Democratic Party — and the subsequent crisis within the party, it has not recovered and is currently a lesser political force. Due to the fragmentation of its leadership and a lack of opposition, it is becoming less of a challenger based on the recent public announcement of its leadership (DP leader Gantumur and his talks about forming a coalition with the main party after the 2024 elections). Consequently, the current one-party dominant system became solidified (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Parties in Parliament since 1992

Source: Data from the General Election Committee of Mongolia

2.2. Perceptions on Vertical Accountability

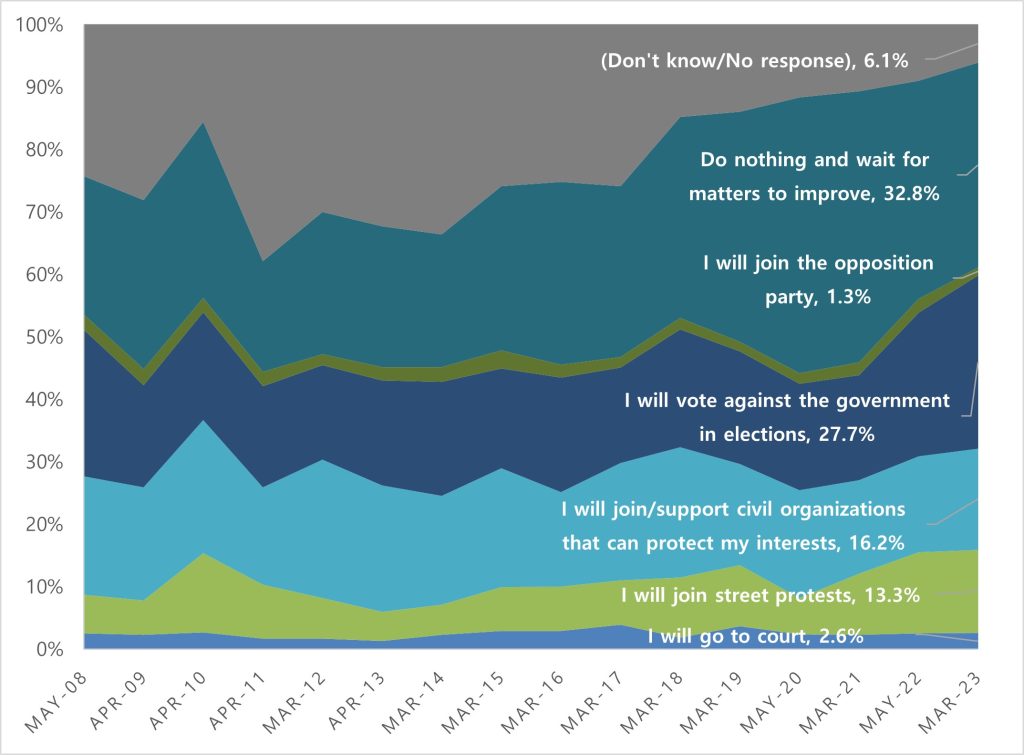

In the end, all these trends contributed to the systematic lack of opposition, and the gradual (re)establishment of the one-party dominant political system. In the previous report on “Horizontal Accountability in Mongolia” (Ganbat and Sumaadii 2024), we concluded that the current system of checks and balances among the government institutions has been undermined. Thus, there is a lack of institutional ways to direct public concerns. In such a context where institutions capable of controlling power are compromised, how can the public form democratic pressure? Existing literature suggests that the challenge of one-party dominant systems is an increasing vulnerability to mass protest (Ulfelder 2005). Indeed, in the current political climate, unless the system evolves in response to the numerous criticisms and addresses its problems with systemic corruption, the only remaining political outlet is citizen’s protest.

Following that, we can deduce that the increasing numbers of protesters in the last few years are a symptom of major institutional deficiencies. Despite 2023 being themed by Mongolian officials as the “year of anti-corruption” over the past few years, Mongolia’s position in various global rankings has steadily worsened. In 2023 Transparency International’s assessments, Mongolia’s corruption ranking further declined from previous years and stands at 121 out of 180 with a Corruption Perception Index of 35, which places it among countries with a serious corruption problem (TI 2024). The Press Freedom Index ranked 88th in 2023 (RSF 2023b). The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index Expert Survey revealed a decline from 35 to 33 points (WJP 2023).

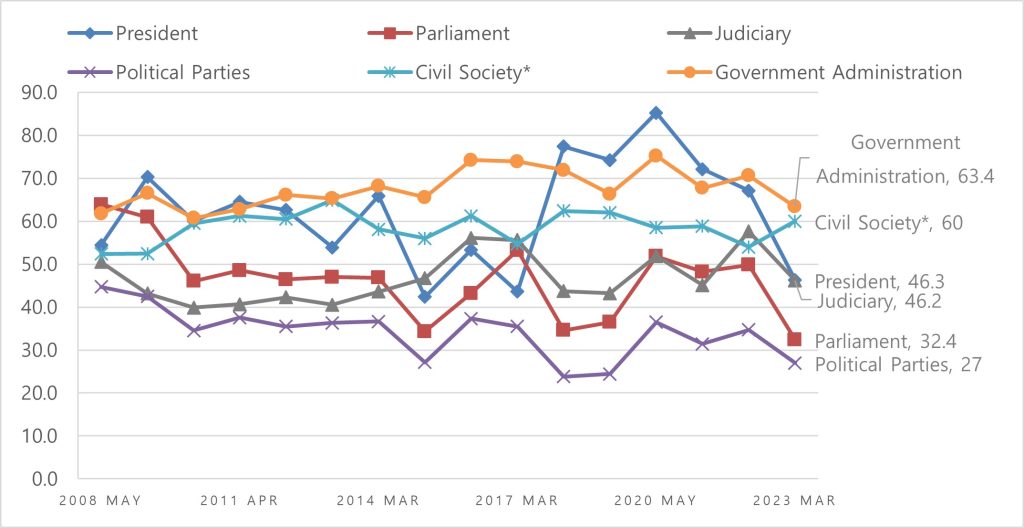

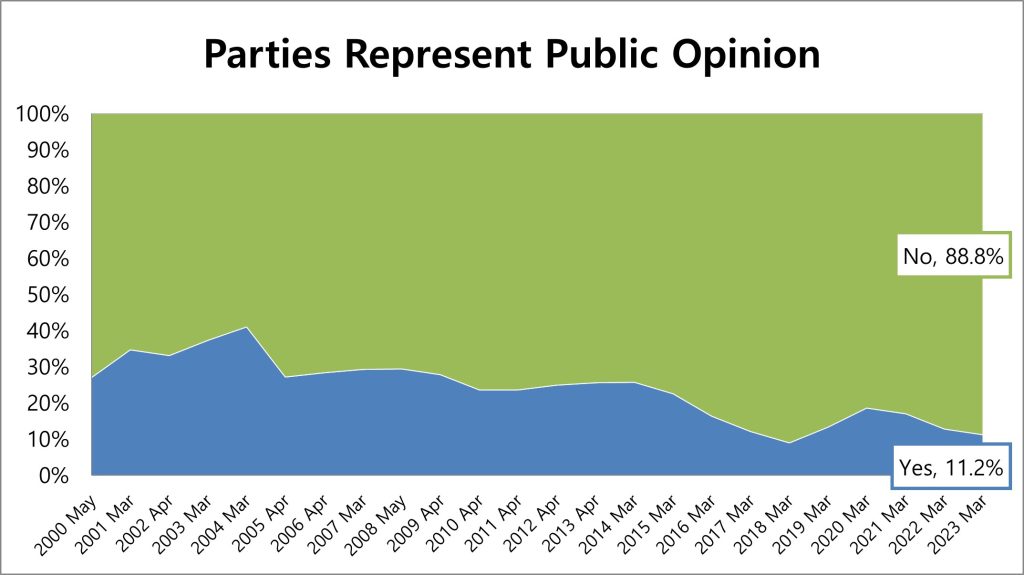

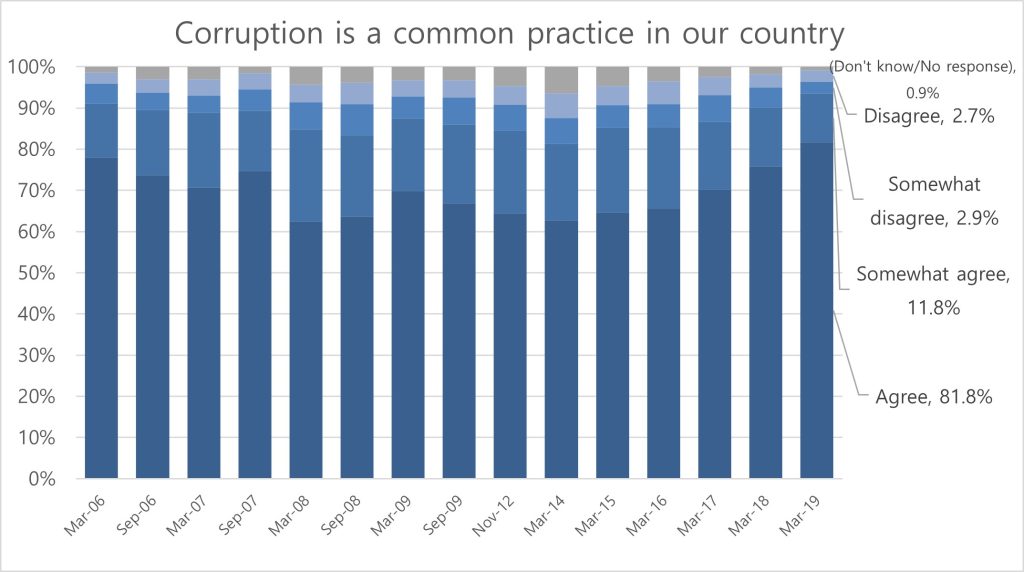

A major challenge related to weak institutions is that systemic corruption is a significant concern for the citizens. Over time, the inability (or a lack of political will) to solve corruption has resulted in a political climate where there is very little public trust in government institutions. Historically, almost all political institutions receive low levels of trust from the population. At the same time, civil society and the government administration received more trust. Notably, the level of trust in the president was fluctuating but was still relatively high until recently. Of particular importance is that political parties are the least trusted of all, and there is a strong belief that current parties do not represent public opinion (Figures 7 and 8). Adding to this is the fact that a majority agrees that corruption is a common practice in the country (Figure 9), thus further fueling public skepticism about government accountability.

Figure 7. Trust in Political Institutions

Source: Data obtained from the Sant Maral Foundation, Politbarometer Surveys 2008-2023

Figure 8. Parties Represent Public Opinion

Source: Data obtained from the Sant Maral Foundation, Politbarometer Surveys 2000-2023

Figure 9. Perception of Corruption

Source: Data obtained from Sant Maral Foundation Corruption Benchmark Survey 2006-2019

Given the prevailing lack of trust in institutional remedies, it is crucial to evaluate the probable actions citizens might take. Long-term surveys reveal a decline in indecision among citizens regarding their response to governmental failures. While a third opt for a passive approach, waiting for improvement, there has been an uptick in those inclined to oppose the government through voting in elections. By 2023, slightly over a quarter of respondents favored this approach. At the same time, there is a rise in those considering protest, with one in seven respondents favoring this option in recent years. It should also be noted that legal channels and joining opposition parties are unpopular, underscoring the skepticism towards institutional solutions. As a result, the citizens do not believe that they can hold the government accountable through any of the institutions and, more importantly, political parties. In the end, elections are left as the main institutional mechanism. In such a context, it is most likely that protest votes will increase, especially in urban constituencies (known to be more radicalized), and newcomers will have a better chance.

Figure 10. What would you do If the government failed to meet your expectations?

Source: Data obtained from Sant Maral Foundation Politbarometer Surveys

Unsurprisingly, the increasing number of protests (with a temporary break during the COVID-19 restrictions) was a symptom of the accumulated institutional deficiencies. The demonstrations about air pollution during the winters of 2015 to 2019 were well organized and had specific goals. There were also protests triggered by corruption scandals such as the “SME Scandal,” the “60 billion MNT Scandal,” the “Green Bus Scandal,” the “Do Your Job” protest, and more recently, the “Coal Theft Scandal,” which saw the protestors storming the government.

In response to the growing tide of protests within Mongolian society, the government reinstated a law dating back to 1994 prohibiting protests on Sukhbaatar Square in front of the Parliament Building. This action only solidified the public perception that the government has failed to effectively address the underlying causes of public discontent and can only resort to banning protests reminiscent of its former communist-style governance. The move further implied an incapacity to engage with criticism and a fear of public unrest.

3. Conclusion

Ideally, the constitution provides a stable framework on which politics can unfold. Yet, the electoral framework introduced distortions between votes and seats and hindered the development of a balanced and equal-opportunity multi-party political system. Over time, the unresolved challenges led to disillusionment in the current establishments’ capacity or willingness to implement genuine reform to improve democratic governance. In a democratic ideal, multi-party systems expand the political choices of citizens and provide more outlets for dissent. To date, the multi-party system has yet to be fully realized. The lack of opportunities for most minor political actors to gain a foothold in the political system led to the dominance of the first two parties and currently, one party. The main problem is that the electoral system needs to evolve to consider transparency, fairness, and inclusivity in the electoral process.

Moreover, there is a considerable lack of accountability and transparency in governance, which introduces significant risks. Among them, the risk of corruption and risk for the quality of governance are considerably high and unlikely to be resolved given the current politicization of the judiciary. Altogether, this adds to the public frustration with the governance and views that the current political elites have reached the limits of their personal capacities, and, therefore, more professionals are needed in the government.

One of the main findings in the public opinion polls of the last few years is that the public has started to demand more professionalism from the government (Iveel M. 2024). “Do your job” was one of the slogans during the youth protest of 2022, reflecting the public sentiment frustrated with the current governance. As noted earlier, for the active part of the population, elections are the main institutional way to hold the government accountable. At other times, protest is becoming increasingly relevant.

Given this, it should also be noted that there are more than enough legal avenues to hold government officials accountable. However, as with much of other legislation in Mongolia, implementation problems exist. In the past thirty years, numerous measures have been introduced to remedy the corruption challenges in the country. More recently, the ‘whistleblower laws’ were attempted. Yet, as with most other legislation, the implementation ran into problems. Generally, since Mongolia has no law protecting whistleblowers yet, the current draft has been under review (for nearly ten years). In the meantime, there are no secure and easily accessible channels for reporting corruption. Thus, anti-corruption activists, whistleblowers, and witnesses are inadequately protected (Jamiyasuren 2023a).

At a procedural level, a typical situation is when a misconduct claim ends in a legal void because it is constantly passed between different agencies until it becomes irrelevant or the claim period expires. Whether it is deliberate or due to general inefficiencies is debatable. However, it is quite common for a misconduct case to enter a so-called “legal oblivion” (Jamiyasuren 2023b). The typical case can involve three to four responsible authorities that delay response; each period of a claim typically lasts from 4 to 12 years or until the claim period expires by laws of administrative and criminal procedures. Most likely until the claim becomes irrelevant or the responsible official is no longer in the related position (ibid.). Unsurprisingly, based on such widespread situations, citizens became highly reluctant to use formal ways of resolving conflicts.

Under these circumstances, vertical accountability in Mongolia is unlikely to improve in the short term. As a result, the 2024 parliamentary elections will be a decisive factor for the future of Mongolian democracy. The stakes are high, and the system has accumulated considerable social tensions. When and how the newly elected officials address them will determine whether the new system can facilitate further institutional change to improve democratic governance, or whether citizens will have to take the initiative into their own hands. ■

References

Buyanjargal, Myagmardorj. 2023. “Parliament Approves Law in a Few Days and Undermines Freedom of Speech!” The UB Post. January 23. https://www.theubposts.com/a/12593 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

CIVICUS Monitor. 2023. “Civil Society Raises Concerns about Detention of Activist and Restrictive Social Media Law as Anti-Corruption Protests Erupt in Mongolia.” March 2. https://monitor.civicus.org/explore/civil-society-raises-concerns-about-detention-of-activist-and-restrictive-social-media-law-as-anti-corruption-protests-erupt-in-mongolia/ (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Dulamkhorloo Baatar. 2023. “Nest Center NGO and MFCC Opposes New Law on Social Network.” Nest Center for Journalism Innovation and Development. January 26. https://www.nestmongolia.org/blog/nest-condemns-new-law (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Ganbat Damba, and Mina Sumaadii. 2024. “Horizontal Accountability in Mongolia: The Challenges of (Counter) Balancing. in Asia Democracy Research Network. 2024. “Horizontal Accountability in Asia: Country Cases (Final Report Ⅰ).” ADRN Working Paper. http://www.adrnresearch.org/publications/list.php?cid=3&idx=353 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Iveel M. 2024. “L.Sumati: Voters Are Waiting for New and Professional Election Candidates.” UB Post, February 24, No.022 (2706) edition.

Jamgansuren, Delgersaikhan. 2023. “Law on Protection of Human Rights on Social Media.” Lehmanlaw Mongolia LLP. February 17. https://lehmanlaw.mn/blog/law-on-protection-of-human-rights-on-social-media/ (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Jamiyasuren, Oimandakh. 2023a. “Whistleblower Campaign ‘…Нэгдье’ – a Paper Fight?!” Mongolia Awakening. August 27. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/whistleblower-campaign-нэгдье-paper-fight-oimandakh-jamiyansuren/ (Accessed April 4, 2024)

______. 2023b. “Kraken System of Mongolia.” Mongolia Awakening. September 11. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/kraken-system-mongolia-oimandakh-jamiyansuren (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Lührmann, Anna, Kyle L. Marquardt, and Valeriya Mechkova. 2020. “Constraining Governments: New Indices of Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal Accountability.” American Political Science Review 114, 3: 811–820. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000222 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Nomin, B. 2024. “Will Tsets Review the Decision to Enlarge Electoral Districts? [Тойргийг томсгосон тогтоолыг Цэц шүүх үү]” Unuudur. February 28. https://www.unuudur.mn/a/265327 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

On the Proceedings of Disputes in the Constitutional Court [Үндсэн Хуулийн Цэцэд Маргаан Хянан Шийдвэрлэх Ажиллагааны Тухай]. 1995. https://legalinfo.mn/mn/detail?lawId=19 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Ooluun, B. 2023. “Parliament Accepts President’s Veto on the Law on Protecting Human Rights on Social Media.” MONTSAME News Agency. March 17. https://montsame.mn/en/read/314889 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Reporters Without Borders: RSF. 2023a. “Mongolia: RSF Urges Legislators Not to Override Presidential Veto of Dangerous Social Media Bill.” March 15. https://rsf.org/en/mongolia-rsf-urges-legislators-not-override-presidential-veto-dangerous-social-media-bill (Accessed April 4, 2024)

______. 2023b. “Mongolia.” December 22. https://rsf.org/en/country/mongolia (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Sato, Yuko, Martin Lundstedt, Kelly Morrison, Vanessa A. Boese, and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2022. ‘Institutional Order in Episodes of Autocratization’. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4239798 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Transparency International: TI. 2024. “2023 Corruption Perceptions Index: Explore the Results.” January 30. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Ulaanbaatar News. 2023. “ASSEMBLY: The number of parliamentary constituencies and mandates for the 2024 regular election was approved [ЧУУЛГАН: УИХ-ын 2024 оны ээлжит сонгуулийн тойрог, мандатын тоог баталлаа],” December 21. https://ubn.mn/p/54373 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Ulfelder, Jay. 2005. “Contentious Collective Action and the Breakdown of Authoritarian Regimes.” International Political Science Review 26, 3: 311–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512105053786 (Accessed April 4, 2024)

Uyan, U. 2024. “The Claim That Established Electoral Districts Violate the Constitutiona Was Referred to the Constitutional Court [Сонгуулийн Тойрог Тогтоохдоо Үндсэн Хууль Зөрчсөн Гэж ҮХЦ-д Ханджээ].” Eguur.MN. February 27. Улс төрийн мэдээ. https://eguur.mn/477856/ (Accessed April 4, 2024)

World Justice Project: WJP. 2023. “WJP Rule of Law Index.” https://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index (Accessed April 4, 2024)

■ Mina Sumaadii is a Senior Researcher at the Sant Maral Foundation, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

■ Ganbat Damba is the Chairman of Board at the Academy of Political Education, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

■ Typeset by Hansu Park, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 204) | hspark@eai.or.kr